By Eline Crijns – Translated by Liz Waters

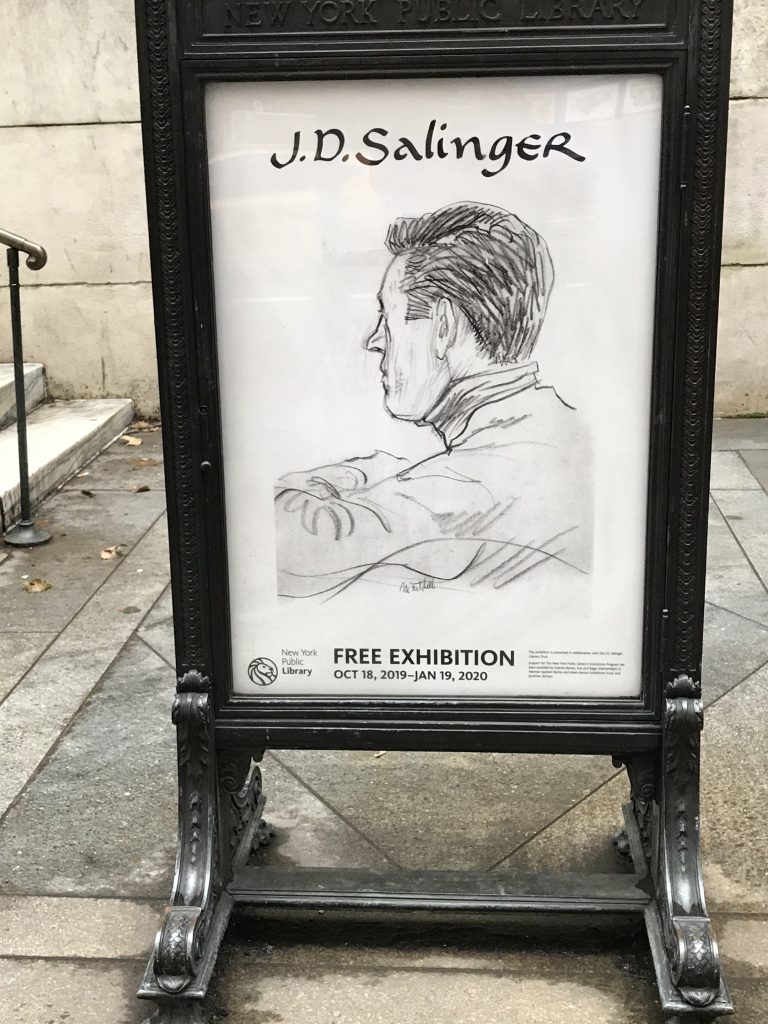

J.D. Salinger (1919-2010), famous for his timeless classic The Catcher in the Rye, has been dead for ten years. Having published nothing in the second half of his life, during which he avoided publicity, he is generally presented as a freak and a weirdo. Wrongly, as can be seen from a recent exhibition in the New York Public Library.

‘I’m the slowest ripener, the slowest maturer I think I have ever run into,’ J.D. Salinger.

Ten years after his death, J.D. Salinger, the author who achieved worldwide fame with The Catcher in the Rye, is still very much alive. The exhibition in Manhattan where previously unseen Salingeriana was on show drew a constant stream of visitors and received extensive coverage in the press. And no wonder. The forty-five years of radio silence from the author were fertile ground on which speculation about his reclusiveness and the absence of new work were able to thrive. A decade after his death, expectations are undimmed and a posthumous comeback is in prospect. The more than two hundred unique pieces of memorabilia in the exhibition testify to his life and allow Salinger to speak as we have never heard him before. The icing on the cake is a scene from the original typescript of The Catcher that was scrapped by the writer. A key scene, it reveals the motivation behind the famous central character’s much-discussed ‘unphony’ use of language, the reason why the book was labelled controversial in its day.

Salinger’s son and widow took the initiative in staging the exhibition in the New York Public Library last winter under the auspices of the J.D. Salinger Literary Trust. It makes clear once again how closely interconnected were Salinger’s life and work. The background decor of his childhood and the environment in which he grew up, his experiences during the war and his profound interest in the mystical aspects of religion had a far-reaching influence on his fiction, while at the same time the overwhelming global success of his work defined his life. Salinger had to pull out all the stops to cope with the constant threat of being swamped by the media and his fans. From his letters, on view for the first time in the exhibition, a picture emerges of a man who was dedicated to his authorship and wanted to continue to devote himself to it without compromise, despite his fame. His rigorous stance and his seclusion far outside the New York literary world, especially as time went on and decades passed, meant that for lack of information, depictions of him in the media grew increasingly absurd: from eccentric to oddball, from hermit to freak.

I have been captivated by Salinger’s oeuvre, but I was dismayed by the tone of the pompous (unauthorized) Salinger biography and film documentary of 2013. They seemed impossible to reconcile with the prose world I was introduced to by Salinger’s books, which fascinated me immensely. Was the work really by the same man? This sense of discrepancy made the exhibition just what I needed. In the well laid out, air-conditioned exhibition space, an almost sacred silence prevails, in which visitors become acquainted with previously unseen memorabilia. As I take an initial exploratory tour of the display cases, knowing what I do about Salinger’s strong views on privacy, the first thing that occurs to me is that he must be turning in his grave. The exhibition could hardly be any more personal and intimate. I make the reasonable assumption that his relatives, on behalf of the Literary Trust, will have respected his wishes, but it feels surreal to see that from the hand of a man of whom the outside world rarely heard anything, whose opinion could only be guessed at, we can now read emotional observations on the Holocaust, which at the time he probably noted down for himself alone. I decide to accept the curators’ openness as the new benchmark for reporting on Salinger.

‘Have sat most of my life away at the typewriter’

In the small exhibition space, where paper predominates in the form of books, typescripts, letters and photographs, it’s the more solid items that catch the eye. The attention of visitors is therefore drawn to tangible things that passed through the hands of this impalpable man. Looking at someone else’s spectacles, coffee mug and pipes immediately feels voyeuristic, even if the person in question is dead; can fingerprints still be warm? His Timex watch in a glass case, stopped at ten past ten, resonates with one of his best stories. In ‘For Esmé – with Love and Squalor’, a stopped watch is movingly consequential. Up near the ceiling the room is decorated with the books Salinger wrote. The many editions, formats and translations into more than thirty languages make a colourful whole. There are plenty of superlatives to describe the success of Salinger’s work, but it was not always so. Given what we know today (more than 65 million copies sold) it may be hard to believe, but Salinger had to peddle his work. Before it was taken up by Little, Brown, The Catcher was rejected by another publisher, and the advance paid was hardly excessive (Rakoff, 2014).

The exhibition’s pièce de résistance is the original typescript of The Catcher in the Rye (ca. 1950/51). It lies open at a page of corrections by Salinger in black-grey pencil. He has even struck out half a page completely, with a firm pencil cross over the lines and ‘delete’ in the margin. Scrutiny of the finished book reveals that this passage (see text box ‘Scrapped’) was indeed omitted from the published version.

In the deleted paragraph, which sees the light for the first time in this exhibition, Salinger has his world-famous protagonist Holden Caulfield explain his use of explicit language. It is precisely this aspect of the worldwide bestseller that has been a source of controversy ever since the book was published, fuel for heated debates and the origin of countless interpretations by literary experts concerning the writer’s motives.

Students of literature worldwide still analyse The Catcher in the Rye. What a writer decides to scrap throws new light on what he published. It gives insight into his way of thinking and into the writing process at a microscopic level, allowing us to engage closely with the literary craft. There is more of a similar calibre. One exhibition case contains the leather folders with typescripts of his stories, open to show Salinger’s corrections. Ideally one would like to leaf calmly through these page by page, but even a visitor’s hand on the glass elicits an admonishing cry from the security guard on duty.

From a business point of view, after the spectacular success of The Catcher Salinger became a more seasoned writer. In a letter to his literary agent Dorothy Olding in 1961 he writes that he wants to negotiate with the publisher about the royalties for Franny and Zooey. He’s eager to generate income for his wife Claire and his children. Salinger claims that the publisher is taking only a limited risk, since demand has already been created. He wants his part in the success and a ‘fair share of the profits for family’. He asks for advice and checks that his wishes are not ‘out of line’. If they are, then he is willing to come down a little, but not too much. ‘Sorry to sound so adamant, but I’m worried.’ Salinger closes by stating that he certainly does want to publish, but if necessary he’s prepared to put the manuscript aside for a few years.

There is no way of knowing how the negotiations ended, since the four original book contracts in the glass cases are not open at the royalties page, a gentlemen’s agreement that the publishers in particular are keen to uphold.

The most frequent question in those decades of silence in which nothing by Salinger was published was whether he was still writing. The correspondence on display lifts the veil. In a letter to his son Matt in France from March 1977, Salinger reflects on his development as a writer and on his productivity. ‘I’m the slowest ripener, the slowest maturer I think I have ever run into, and a very great part of my long and bumpsy professional life has been spent in a kind of daily watchful attendance for certain kinds of ripening processes to set in.’

In a letter to his old army comrade Jack Altaras a year later, he mentions his daily writing routine. ‘As for me, I’m well, and doing what I usually do. Have sat most of my life away at the typewriter, some might say. True enough, but it’s been a matter of preference. The last ten years, especially, have been quiet and very good, and have a lot of work done, which I suppose I will eventually publish.’

Salinger wrote, and Salinger carried on writing. That much is clear – or rather, in the exhibition it is made clear straight from the horse’s mouth. His son confirmed it in an interview with The Wall Street Journal to mark the opening. ‘He continued to write for more than six hours a day until his death in 2010.’ In response to the crucial question of what all that writing produced, Matt Salinger answers that he is still busy with his father’s notes and typed work. ‘It will take another five to seven years before new work is published.’

‘I still rejoice, if unofficially, every day of my life to be restored to civilian status’

The exhibition shows the degree to which Salinger’s fiction was inspired by his life. The background and events from his earliest childhood and his adolescence, from his army experiences to his religious interests in later years: all of it is woven into his stories. Salinger grew up in the Manhattan of the twenties and thirties. After various addresses on West End Avenue he moved at the age of thirteen with his parents and older sister Doris to 1133 Park Avenue, in the well-to-do Upper East Side. Most of what Salinger wrote takes place in that part of New York. The key scenes in The Catcher in the Rye are set in and around Central Park, the back garden of Salinger’s childhood. The Glass family of his other stories, of which the wayward, extraordinarily intelligent and highly sensitive offspring are unforgettable, live in an apartment in that same district.

In 1934, fifteen-year-old Salinger found himself at Valley Forge Military Academy. He’d been performing none too well at school and his parents had decided he needed structure. There he started to write fiction. He wrote for the yearbook and the school newspaper, and when he got his diploma two years later his only ambition was to be published in The New Yorker.

Salinger’s experience of combat in the Second World War had a profound influence on his life and work. In his stories the war continually seeps into the lives of the main characters and those closest to them. Salinger’s participation in the war is given a prominent place in the exhibition. The organizers have taken to heart a letter his son Matt received after Salinger’s death in February 2010. ‘He was in every sense a hero-something,’ writes John L. Keenan, former army comrade and friend of Salinger. ‘He was brave under fire and a loyal and dependable partner,’ he adds.

Keenan claims that after Salinger’s death the media wrote mainly about his work, his place in American literature and his lifestyle, but little about the four years he spent in the army serving his country. Salinger was in the Counter Intelligence Corps. The conflict began for him on D Day, 6 June 1944, when he took part in the Allied landings on Utah Beach on the Normandy coast and witnessed the loss of huge numbers of troops.

Further decisive parts of his wartime experience were the Battle of Hürtgen Wood and the horrors he encountered in the concentration camp Kaufering IV when it was liberated. In 1993 The New York Times published a letter entitled ‘US Can’t Feel Proud of Holocaust Role’, in which a reader argued that although American troops liberated Europe, ‘we didn’t liberate the Holocaust victims’. Salinger stuck the cutting to a sheet of paper and wrote next to it, ‘True! No liberating was done. None. Governments, “statesmen”, nations, citizens, the world over, just looked the other way or themselves felt comfortably unendangered.’

It is striking to say the least to read such a firm statement in the handwriting of the man who for decades shrouded himself in silence and by whom I did not expect to be presented with a personal opinion – let alone on such a subject. During the war Salinger lugged his typewriter with him everywhere and wrote the manuscript of The Catcher. The exhibition shows that Salinger carried the war with him all his life. He remained friends with the comrades he’d shared a jeep with, calling them ‘jeepmates and Huertgen Forest types’, and corresponded with them regularly.

In a letter to Jack Altaras from 1978, Salinger tells of a trip he took with his son Matt on which they drove through Normandy villages as a kind of ‘down war-memory lane’. According to Salinger, much remained unchanged, except that there were no longer any dead cows in the meadows with their legs stuck in the air. He counts his blessings: ‘In a rented BMW wearing a white shirt, a gray suit. And with one’s son. It seemed a quiet but sizable little victory of some sort. Felt very grateful. … I think I still rejoice, if unofficially, every day of my life to be restored to civilian status.’

In the early 1950s Salinger read The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna and started to study the Vedanta religion seriously. He was attracted by the mystical aspects of eastern religion in particular. The notebooks on show contain texts drawn from oriental wisdom and various other mystical belief systems, both in his handwriting and typed and stuck onto the pages.

In a 1976 letter to his son, who was studying in France at the time, Salinger recalls something that happened during his time in Vienna when he was eighteen. ‘Walking down a foreign street alone with my overcoat open, stopping at a stand-up counter and having a goulash sandwich and a glass of dark beer in the middle of the overcast fall afternoon. Happiness. … At certain moments, for “no reason”, the cup runneth over. One day, no doubt, you will be drunk on non-dualist Vedanta philosophy just like me.’ As he did with his son, Salinger gladly – or inevitably – shared his religious insights with his readers. His fiction is peppered with them.

Salinger’s reclusive years in Cornish, New Hampshire, are depicted in photographs from the period 1970-90 in which Salinger can be seen in the garden, on a boat, or on the beach with his children and later his grandchildren. Family snaps show him as a person – in colour, which brings him closer to the present day. ‘In Cornish Salinger lived simply and unostentatiously’, according to the description given of the photos. It is a unique experience to read Salinger’s own reflections on a period during which the world heard nothing from him. In a letter to his son in high school in 1974 he writes that he has been to his mother’s apartment in New York to fetch boxes of material about himself, and he describes his years in Cornish as follows. ‘Reading through all those old papers and letters yesterday made me all the more aware how happy and relieved I am to be living in the present, not the past. … These Cornish years have been what I would call my real life. Oui.’

The right to stew in your own juices

I walk a block from the house of Salinger’s teenage years on Park Avenue to Central Park, a walk he must have taken many times in his childhood. His trail leads me to the big lake, where I establish that the ducks don’t go anywhere in winter – a question about which Holden Caulfield in The Catcher racked his already teeming brain.

I continue my walk to the American Museum of Natural History – a place of inner tranquillity for Holden – and contemplate the exhibition. Salinger’s voice has become distinctly audible, that is the main effect. It was almost chastening to be able to read his words straight from the source, from his own letters, unfiltered, unhindered by the interpretations and veils of third parties having their say about him.

Naturally the organizers have thought carefully about the image of Salinger that emerges. Some things were not on show. There was no correspondence with his daughter, nor with lovers and exes (his widow was his third wife). That does not alter the fact that showing material from Salinger’s own hand creates an entirely different impression from that which emerges in the aforementioned biography.

The biography, for lack of collaboration by Salinger and those close to him, relies on testimony from others and a colourful range of opinions and hearsay from people who in many cases had a troubled relationship with the writer. Salinger’s voluntary seclusion is alleged throughout the book to be a thorn in everyone’s flesh, and its conclusions on the subject are presented in reproachful tones as ‘conditions’ from which the writer is said to have suffered.

Who determines, though, that as a bestselling writer you are public property? Does such success necessitate giving up your right to privacy? Salinger drew the line himself and maintained it rigidly, probably knowing it would never be enough, that the media and fans are insatiable. He was faced with great hordes of them worldwide, especially in the years after the publication of The Catcher and again in 1980, when John Lennon’s murderer explained his motives with the book in his hand.

Was Salinger with his lifestyle a recluse, and in what sense of the word? ‘He just decided that the best thing for his writing was not to have a lot of interactions with people, literary types in particular. He didn’t want to be playing in those poker games, he wanted to, as he would encourage every would-be writer to do, you know, stew in your own juices,’ Matt Salinger told The Guardian in 2019.

The exhibition supports the image of a man with a relatively normal social life, with family, friends and old army comrades, and a field of action in which he corresponded with his editors, with his literary agent and with writers who had become friends. This replaces the impression of a freaked-out hermit with that of a man of flesh and blood who tried to live as normal a life as possible, while also attempting – if not to everyone’s satisfaction – to be as uncompromising a writer as he could be.

We have to hand it to him that he was brave enough to resist being led by his ego and to refuse to succumb to the attention that fame brings. He took that too far; unsparing bluntness towards the outside world seemed to be the only weapon he obstinately reached for, never yielding an inch. In a letter to Laura Norton, daughter of his army mate Tom Norton, Salinger stressed that his army comrades know him as he truly is and that he has always been that way. ‘I’m a little short on Privacy, and have been for years and I’d like to hang on to what little I still have.’

My sympathies go out to someone who was able to hold his own as a ‘literary icon’ and remain faithful to his life and his writing. Despite the openness of the exhibition, we have a right only to what Salinger himself gave the outside world: his fiction. He indicated that everything he had to say can be found in it. My Salinger quest ends at the carousel on the south side of Central Park, the spot where Holden Caulfield in The Catcher ends his story. In the pouring rain he watches his sister Phoebe, who is riding the merry-go-round, from a bench. ‘It was just that she looked so damn nice, the way she kept going around and around, in her blue coat and all.’

Scrapped

Text removed by J.D. Salinger from the original typescript of

The Catcher in the Rye:

‘Right now, though, I want to warn you about something. I think there’s going to be quite a lot of swearing and sexy stuff in this book. I can’t help it. You’ll probably think I’m a very dirty guy, and that I come from a terrible family and all, but I can’t help it. The trouble is, everybody I know swears all the time. And everybody’s pretty sexy. It isn’t my fault. I swear quite a bit and I’m pretty sexy myself, but it’s mostly habit. The thing is, I told my brother D.B. I was going to write a book and all, and he made me promise I’d write it very unphony. So that’s what I’m doing. If you don’t like it, you don’t have to read it. I mean it. You won’t hurt my feelings. What I’ll do, though, if you do read my book, I’ll do something that’ll partly make up for all the swearing and sexy stuff. I’ll tell you things I’ve never told anybody in the world except maybe my brother D.B. or my kid sister Phoebe. I really will. I mean I’ll write the book as if you were a terrific friend of mine. Even though you may be a terrific bastard, for all I know.’

_________

- This article is the English translation of the Dutch version published in HP/De Tijd on 21 april 2020.

- Also available is a more elaborate version of this research article on request by the author.